Artist tells the story of oil and gas development through embroidery

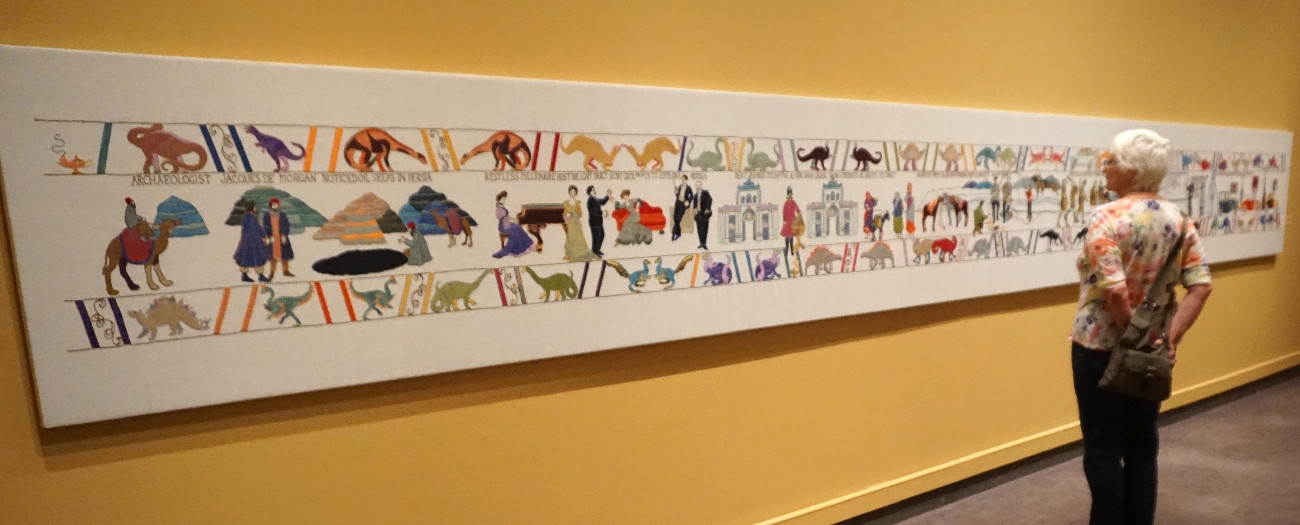

Alberta - July 24, 2018Most of us know at least some of the story of oil and gas development, and how vital it has become to our existence. But you haven’t had the story recounted quite like this—through elaborate, hand-stitched embroidery on over 200 feet of linen.

The Black Gold Tapestry took Calgary artist Sandra Sawatzky 1700 hours over a nine-year period to create, which she breaks down as four years of research and drawing, and five years of stitching. To get it ready for its first exhibition at Calgary’s Glenbow Museum, the last three of those years meant over nine hours a day, seven days a week, of pulling needle and thread through fabric, section by section.

“I was so happy when Friday would come,” says Sawatzky. “I didn’t work on Friday nights, but every other night I worked. You really appreciate your free time when there’s very little of it.”

Sawatzky’s telling of the story of oil begins with the long-gone dinosaurs, whose images border the entire 220 feet of the linen, and ends with a scene familiar to all of us—gas pumps. In between the first and eighth panels, stitched in colourful wool and silk thread, is more than 220 million years of discovery, invention, controversy, and war that brings us to the oil and gas industry we know today.

“We only see this end of the story,” explains Sawatzky. “We don’t think about all of the different choices people had made based on what they have and what they know—it keeps us thinking, fretting, about how we can make things work.”

While it’s a challenge to narrow down a sample of “highlights,” below are some intriguing vignettes from the tapestry:

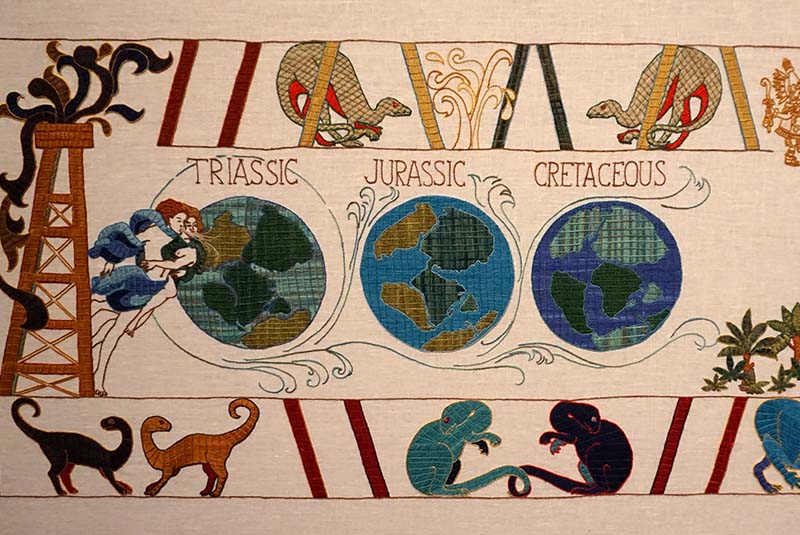

Hydrocarbons are brought to you by the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods, and beyond. The first scene takes you back to the very beginning, explaining that over hundreds of millions of years the organic matter and sediment that settled has decomposed into coal and oil and gas deposits. People once thought that the decomposing dinosaurs were what transformed into hydrocarbons, a notion disproved long ago.

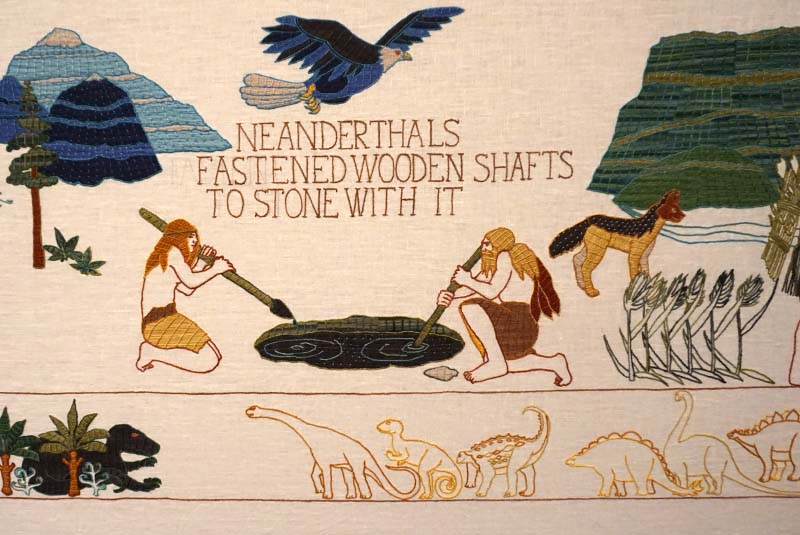

Bitumen. Stick. Tool. Sawatzky stitched scenes of oil flowing to the surface and being used by Neanderthals to make hunting tools, and of ancient Mesopotamians using the bubbling crude as waterproofing material for boats, as medicine and cosmetics, and as an ingredient in bricks used to build the massive structures known as ziggurats that would cause any architecture enthusiast’s jaw to drop.

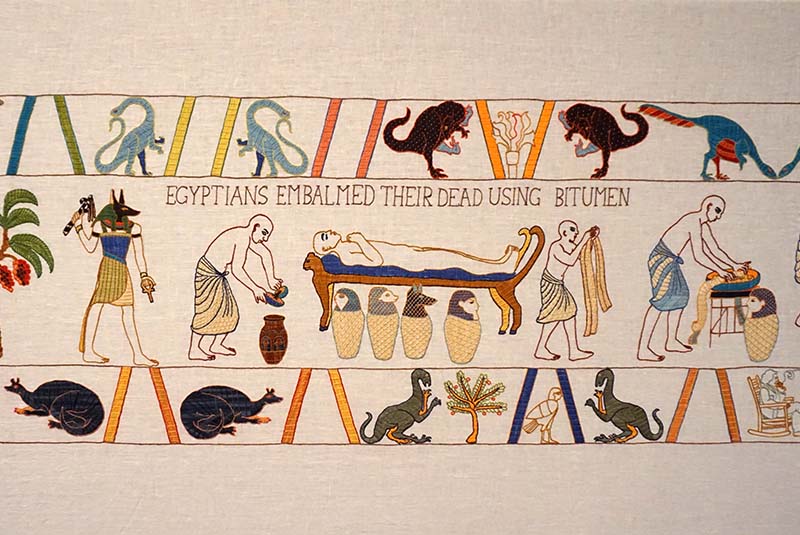

Embalm like an Egyptian. Last year, Alberta exported 83 per cent (17 per cent stayed within Canada) of its 2.8 million barrels per day of bitumen to the United States, but this isn’t something unique to our times. Back when Egyptians were mummifying their dead—both humans and animals—bitumen was imported from the Dead Sea to coat mummy wrappings and to fill body cavities.

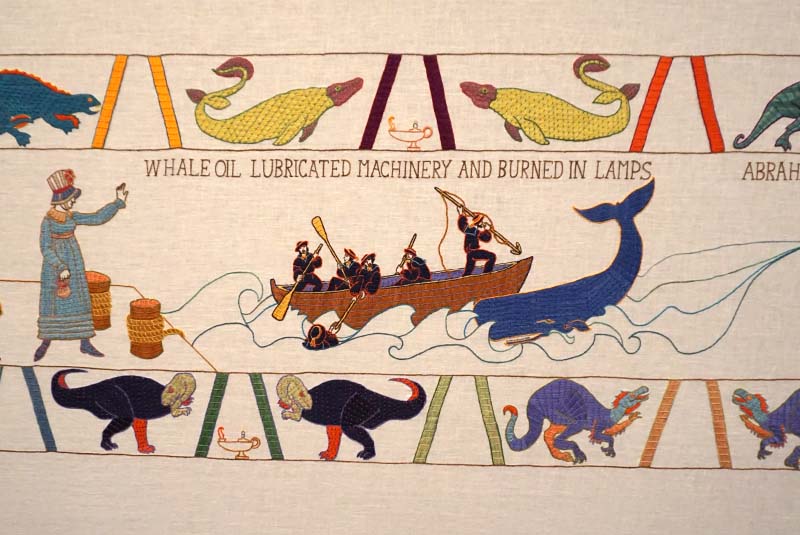

Kerosene and a Canadian saved the whales. Before the development and distribution of any petroleum product, whale oil was widely used to fuel lamps and to run machines. This demand for whale oil meant that millions of whales were hunted between the 18th and 20th centuries, but once Canadian scientist Abraham Gesner invented kerosene from coal, bitumen, and oil shale—and kerosene was less expensive than whale oil and burned bright and clean—the practice of hunting whales for their oil subsided.

Pipelines and oil tankers. In the 1870s, long before any controversy, Azerbaijani brothers Robert and Ludvig Nobel built the first pipelines to transport a product they were distilling from petroleum: kerosene. Later on, those same brothers came up with the idea of moving their petroleum product by ship. The first oil tanker was named the Zoroaster.

A good egg. Stewart Herron, a Canadian businessman, lit gas that was seeping from a crack in the ground near Alberta’s Sheep River and used the fire to fry eggs to demonstrate the escaping gas’s potential to a few prominent locals. The demonstration worked, and the men joined Herron in forming one of the companies that would play a crucial role in the Turner Valley boom—Calgary Petroleum Products Company. At least that’s the story. Interestingly, Alberta’s oil boom of the 1920s and 1930s, wild and unruly as it was, is what led to the creation of the province’s energy regulator in 1938. July 2018 marked the 80th year of energy protection and regulation in Alberta.

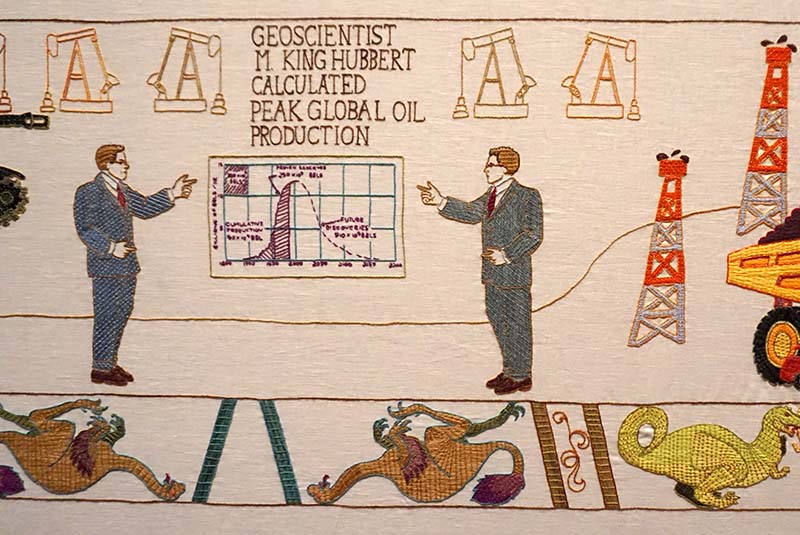

Nostradamus had nothing on Hubbert. A geoscientist who worked for Shell predicted that the world would eventually run out of easy-to-extract oil. M. King Hubbert specifically saw this happening near the end of the 20th century, which was, in fact, when Alberta’s oil sands were being developed for their hard-to-extract but abundant bitumen.

Seeing the tapestry in person is highly recommended. No matter how high the resolution, or how vivid the colours, no picture or video image does this piece justice. Unfortunately, the eight panels of gorgeous linen have left Calgary’s Glenbow Museum. However, Sawatzky is working with supporters to coordinate a travelling exhibition for the tapestry.

Cassie Naas, Writer