How Turner Valley gas flaring ushered in an era of regulation

Alberta - January 07, 2019Below is an excerpt from Steward, a book published by the AER’s predecessor, the Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB), to mark 75 years of energy regulation in Alberta. This is Part 2 of a two-part telling about how wasteful flaring of natural gas in the Turner Valley, Alberta area prompted the Alberta government to create an oil and gas regulator. Part 1 ran last month.

… That was the atmosphere surrounding the Alberta government’s decision to create a watchdog for the energy commons. Braced for a fight, the provincial cabinet recruited William F. Knode, a veteran of the Texas Railroad Commission’s conservation battles, as the ERCB’s first chairman. “Bill Knode was a rough, tough individual,” Connell said. “But he got the board started. It was necessary to take some fairly tough measures in the beginning.”

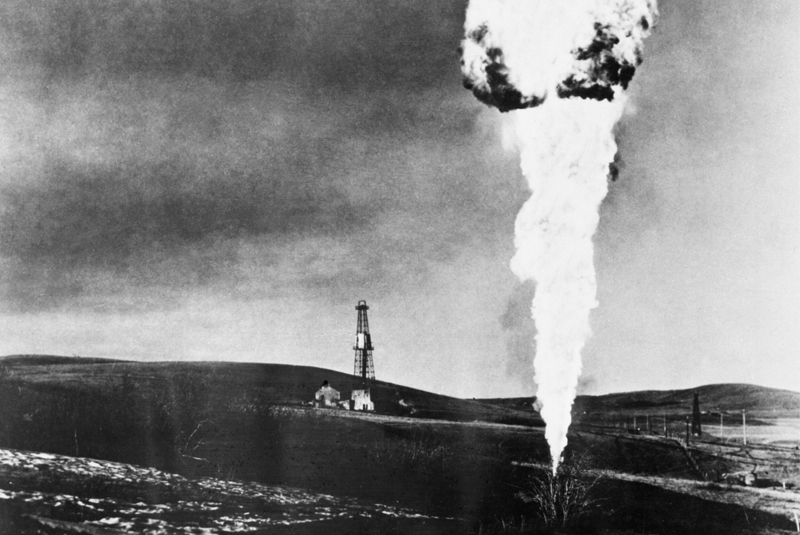

In ERCB oral history interviews thirty years later, Knode said attitudes in Alberta echoed what he’d seen in Texas. “The oil man had a peculiar mental block against gas,” he said. “You would see flares all over an oilfield. I mean you’d see them for miles, maybe not concentrated like in Turner Valley, but very comparable per barrel of oil produced against the total gas wasted.”

Turning Off the Gas

The waste and the opposition to interference are well documented — most graphically in testimony collected during a 1933 lawsuit that stopped the first attempt to impose order on the youthful industry. “Very little more than 10 per cent of what passes out of the wells is, except for the recovery of naphtha, applied to any useful purpose,” said the Supreme Court of Canada in its final verdict against the Alberta government in the case Spooner Oils Ltd. v. Turner Valley Gas Conservation, [ 1933 ] S.C.R. 629. …

Personally and professionally, “I became fascinated with your country and the potential,” Knode said. Tapping that potential, however, required huge shifts in mindset. “You had to educate the producers to the probable benefits of conservation, the maximum recov¬ery from the reservoirs and both above-ground and underground prevention of waste.”…

Persuading Alberta entrepreneurs to practice the care the scholars preached turned out to be a long mission. “It was more or less just scientific research to the fellows here. It was an educational program, the first two years,” Knode said. “The first steps were to get the producers to go along with the idea that this conservation was to the benefit of the reservoir, and to prove to them that the future potential of the gas was much greater than the little bit of condensate they were recovering. This of course met with a lot of resistance.” …

The conflict in Turner Valley shook the foundations of early oil wealth. As Chief Justice Lyman Duff observed, “The effect of the order of the Board upon the operations of the company has been to reduce its production of naphtha by something like 95 per cent.”

The Turner Valley board’s contested directive, known as Order Number 1, tried to give meaning to a 1930 political triumph: a transfer agreement giving Alberta title to its natural resources. … The Supreme Court said conservation was possible in principle, but in practice the opening move stumbled over two obstacles. First, the transfer agreement failed to specify that new provincial rules applied to mineral leases granted by the federal government before 1930. Second, Alberta needed to do more than appoint a local watchdog over one industry hot spot. To make conservation stick, the province had to spell out that wasteful old customs were no longer acceptable, and that the new standards applied across its entire 537 000-square-kilometre natural resource commons.

The Supreme Court’s ruling turned out to be a tall order. Regime change came first: in 1935, Social Credit ousted the last United Farmers of Alberta government, which was distracted and shaken by scandal and the Great Depression. Next came prolonged efforts to catch the attention of the government in Ottawa. Then, after an amendment to the natural resources transfer arrangement established the province’s authority, the legislature passed two versions of the bill creating the ERCB before the government’s lawyers were satisfied that any future protest lawsuits could be repelled.

Before tightened regulations, a 1920s Turner Valley burns off gases, wasting valuable resources

Public hearings on the legislation sent industry a message that the province meant to enforce waste reduction. … When oil entrepreneurs — teamed up as the Alberta Petroleum Producers Association, with former UFA premier Herbert Greenfield as president — demanded promises that business would not be hurt, Knode stood firm: “If the legislature cannot secure conservation in Turner Valley by an act administered by a board, then it is my recommendation that the government take over operation of the field itself. This is a matter of utmost importance to the government and to the people of the province.” The legislation passed with only one change requiring study of a compensation scheme for firms hurt by waste control.

The debate boiled over into confrontation. For public consumption, resistance leaders stuck to formal rhetoric. Model Oils managing director W.C. Fisher, for example, branded the province’s actions as “con¬fiscation and expropriation.” The clash of powerful personalities in the climax of Alberta’s oil range war occurred out of sight of the rudimentary 1930s news media, and no shots were fired. But insiders who knew said the drama bordered on violent. Oral tradition among political and business leaders preserves this confrontation as the final act in establishing the ERCB’s authority. …

William Epstein, a Calgary lawyer who rose into international practice with the United Nations, like¬wise never forgot his early experience with the ERCB and Knode. “He was a rough diamond,” said Epstein. “He really was polite but a rough diamond and he didn’t know anything about the law. He was just a man in the field who understood oil and conservation.” Albert Mayland — a leader of industry resistance — was just as hard, Epstein added. “We turned all these wells off and put seals on them, and we warned them that if they took off these seals, by God they would be prosecuted. Mayland was a guy who challenged the government — a real tough baby.”

The faction of independent oil entrepreneurs led by Mayland eventually gave up on defying Knode’s crew only because the government took away the weapon Spooner used to stop the province’s first foray into regulation. The 1933 court defeat inspired an amendment in 1938 to the ERCB’s founding legislation, banning court appeals of its decisions.

Resource Editor